The History of Tantra: From Ancient Traditions to Modern Practice

The History of Tantra: From Ancient Traditions to Modern Practice

A Timeline-Style Exploration

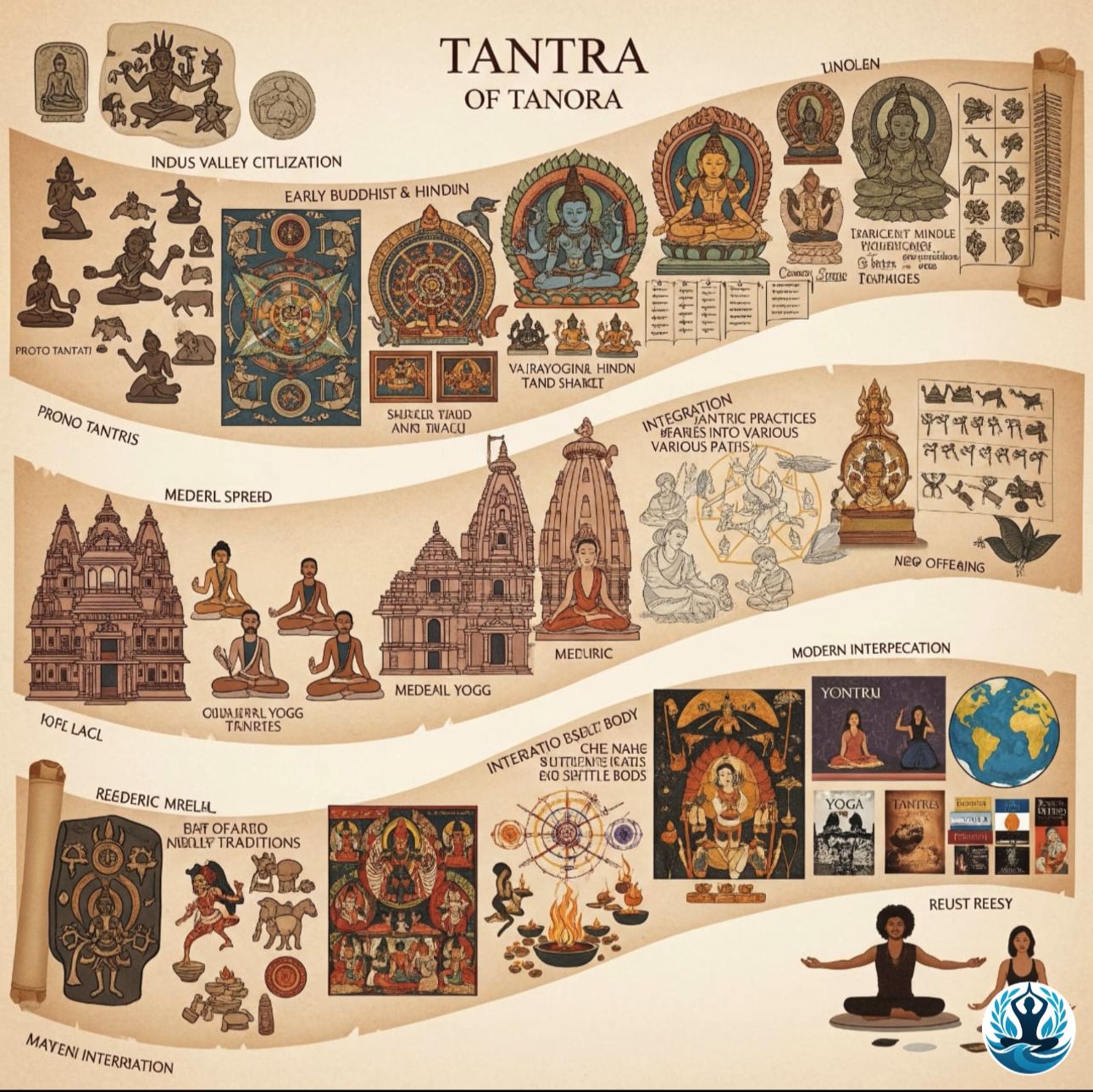

1. Pre-Tantric Foundations (Before 500 BCE)

Before Tantra emerged as a distinct spiritual system, India already had a rich spiritual landscape:

Vedic Traditions: The Rigveda (c. 1500–1200 BCE) and later Vedic texts were steeped in ritual, hymns, and fire sacrifices (yajnas). These early practices laid the groundwork for concepts of mantra, ritual purity, and the nvocation of deities.

Proto-Shakta Worship: Archaeological evidence from the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 2500–1500 BCE) shows figurines and seals that hint at early mother goddess worship and fertility symbolism — elements that would later become central in Tantra.

Yoga and Meditation Roots: Early ascetic and meditative practices — the precursors to later yogic systems — began forming, focusing on breath, stillness, and inner concentration.

Key Themes Emerging:

* Ritual as a means of connecting with cosmic forces

* Sacred symbols and early deity worship

* Breath and bodily awareness as spiritual tools

2. Early Tantric Seeds (c. 500 BCE – 200 CE)

The foundations of Tantra began to sprout in the later Vedic and early post-Vedic period.

Upanishadic Influence: The Upanishads shifted focus from external ritual to inner realization — ideas of Brahman (universal consciousness) and Atman (individual self) fed into Tantric non-dualism.

Buddhist and Jain Asceticism: Both traditions influenced the Tantric focus on discipline, meditation, and liberation beyond the cycle of rebirth.

Fertility & Shakti Cults: Local village rituals honoring female deities (Shakti) and nature spirits merged with evolving Hindu thought.

Key Concepts Taking Shape:

The divine feminine as the source of creation

The body as sacred, not an obstacle to enlightenment

Early visualization and mantra chanting

3. Classical Tantra Emerges (c. 200 – 600 CE)

This is when Tantra truly started crystallizing into a recognizable system.

Agamas & Tantras: The earliest Tantric texts appeared — scriptures like the Shaiva Agamas and Shakta Tantras outlined rituals, deity worship, and esoteric philosophy.

Shaiva Tantra: Centered on Shiva as the supreme consciousness, often worshipped alongside Shakti.

Shakta Tantra: Focused on the goddess in her many forms — Durga, Kali, Parvati, Lalita — as the ultimate reality.

Vaishnava Tantra: Integrated Vishnu and Lakshmi worship within a Tantric framework.

Buddhist Tantra (Vajrayana): Developed in India and spread to Tibet; emphasized mantra, mandala, and yogic visualizations to achieve enlightenment swiftly.

Distinctive Features Now Established:

* Initiation (diksha) into secret teachings

* Use of mudras (ritual gestures) and yantras (geometric diagrams)

* Sacred sexuality as one of many paths to awakening, not the core focus

4. Tantra’s Golden Age (c. 600 – 1200 CE)

During this period, Tantra flourished as a living spiritual science across India, Nepal, and beyond.

Kashmir Shaivism: Philosophers like Abhinavagupta wrote extensive works blending metaphysics, aesthetics, and ritual practice.

Bengal & Assam Shaktism: The worship of Kali, Tara, and Kamakhya reached its zenith, with rich temple traditions and elaborate festivals.

Buddhist Vajrayana Expansion: Tantric Buddhism reached Tibet, Bhutan, and Mongolia, producing lineages that remain active today.

Alchemy & Medicine: Tantric practitioners experimented with herbal alchemy, metal elixirs, and yogic techniques for health and longevity.

Integration with Arts: Tantra influenced music, dance, sculpture, and temple architecture — particularly erotic temple art (e.g., Khajuraho, Konark).

Cultural Highlights:

* Royal patronage in various kingdoms

* Creation of monumental temples with Tantric symbolism

* Cross-pollination between Hindu and Buddhist Tantra

5. Period of Secrecy and Decline (c. 1200 – 1700 CE)

The Islamic invasions and later Mughal rule altered the cultural climate:

Shift to Clandestine Practice: Tantric rituals went underground due to social and political instability.

Syncretism: Some Sufi mystics interacted with Tantric yogis, leading to shared practices of chanting, breathwork, and ecstatic devotion.

Esoteric Lineages: Teachings were preserved through guru-disciple transmission rather than public temple rituals.

While Tantra lost public visibility, it survived in rural, monastic, and secretive circles.

6. Colonial Period & Early Misinterpretations (1700 – 1947 CE)

With European colonization came a dramatic shift in how Tantra was perceived:

Orientalist Scholarship: British scholars translated Tantric texts but often misunderstood them, focusing narrowly on sexual rites.

Missionary Bias: Christian missionaries condemned Tantra as “degenerate” due to its frankness about the body and its rituals.

Bengal Renaissance: Figures like Ramakrishna Paramahamsa preserved and reframed Tantric spirituality within a devotional (bhakti) context, making it more palatable for a modern audience.

Occult Revival in the West: Theosophists and mystics began blending Tantric ideas with Western esotericism.

7. Tantra in the Global Spotlight (1947 – 1980s)

After Indian independence, Tantra began resurfacing in academic, spiritual, and popular culture:

Scholarly Rediscovery: Indian and Western academics began studying Tantra with more cultural sensitivity.

Neo-Tantra Movements: In the 1960s–70s, Western spiritual seekers reinterpreted Tantra through the lens of the sexual revolution, often emphasizing sacred sexuality over its broader spiritual framework.

Notable Teachers: Figures like Osho, Swami Satyananda Saraswati, and Margo Anand brought Tantric-inspired teachings to international audiences.

8. Contemporary Tantra (1990s – Present)

Modern Tantra exists in multiple streams:

Traditional Tantra: Still practiced in temples, monasteries, and by lineage-holding gurus in India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Tibet.

Neo-Tantra: Popular in the West; emphasizes intimacy, conscious touch, and emotional healing, often with workshops and retreats.

Therapeutic Tantra: Integrated with psychology, breathwork, somatic therapy, and trauma healing.

Secular Adaptations: Mindfulness, yoga, and energy work inspired by Tantric principles but stripped of religious context.

Key Philosophical Threads That Persist Across Time

1. The Body as Sacred – A vehicle, not a hindrance, for spiritual awakening.

2. Union of Opposites – Shiva (pure consciousness) and Shakti (dynamic energy) as the eternal dance.

3. Mantra, Yantra, Mudra– Tools to align the practitioner with cosmic forces.

4. Initiatory Transmission – Authentic learning through a teacher-student relationship.

5. Non-Dual Awareness– Liberation is realizing there is no separation between the divine and the self.

Modern Challenges & Criticisms

Misrepresentation: In the West, Tantra is often reduced solely to sexual practices, ignoring its vast ritual and philosophical scope.

Cultural Appropriation: Traditional practitioners criticize the commercialization and decontextualization of sacred rites.

Preservation vs. Evolution: The tension between keeping ancient traditions intact and adapting Tantra for modern needs remains ongoing.

Conclusion: From Ancient Roots to Global Practice.

Tantra’s journey spans over two millennia — from its sacred beginnings in early goddess worship and Vedic ritual, through its philosophical flowering in medieval India, to its quiet survival during political upheaval, and finally, its re-emergence in modern global consciousness.

Today, whether practiced in the ritual-rich temples of Varanasi, the mountain monasteries of Bhutan, or the intimacy workshops of California, Tantra continues to carry its timeless essence:

A path that honors energy, embodiment, and the unity of all existence.